WORDS Leroy Wallace

ILLUSTRATION Jamie Leigh O’Neill

I’ve been writing about technology for long enough to be cynical about any new fads, but I can still remember the thrill of being one of the first people I know to have a Facebook account. Although this now sounds about as as stupid as boasting that you were the first boy to go wee wee, when the site launched it was restricted to graduates from a small number of elite American universities, and a sprinkling of randoms like myself who knew them online.

At the time it merely felt like a less irritating version of MySpace, or Friendster without the sex pests, and never in my weirdest cheese dreams did I imagine the site would be accused by politicians of tipping the scales on the most farcical election in recent memory. I also never thought I’d need to block my mum for sharing sexy memes of Patrick Stewart, but that’s the strange new world we live in.

The internet was built to survive nuclear war, not share cat pictures, but historic messages from the scientists and army guys who first went online demonstrate an early potential for light-hearted human to human communications. Email was a world changing invention, but also kind of obvious to anybody who has ever posted a letter – the real innovation turned out to be the group communications that evolved on bulletin boards, internet forums and eventually in walled gardens like AOL chat and Compuserve. Non-nerds will already be scratching their heads at these references, which is why the first person to market an accessible way for normals to interact online was destined become very, very rich indeed. After a few false starts the modern concept of the social network was set in stone by goblin-faced boy king Mark Zuckerberg, and at last everybody in the world could theoretically be friends with people from the other side of it. Except, we’ve now come to realise, Facebook likes to make money – and it turns out that just as there’s gold in sharing cat pics, there’s profit to be made from a 500 post argument with your racist aunt, which involves ten of your family members jumping in, wedding invites being withdrawn, and threats of physical violence from cousins who “liked” Katie Hopkins.

Where there’s muck, there’s brass

The current scandal around Facebook, and the title of this piece, hinges around us asking how it is that an argument with your racist aunt can possibly have financial value to anybody – regardless of its hilarity to onlookers. An answer is given by a less humorous example, which is the accusation that Facebook allowed shady research companies such as Cambridge Analytica to indiscriminately mine huge quantities of your personal data so that you could be targeted by advertisers. Some advertisers might just want to sell your Aunt a wolf fleece and some fridge magnets, but some might want to drip information into your news feed in a manner that could sway enough people to vote a certain way. The data from this interaction isn’t just what you publicly say to your Aunt, but every private message you send about the subject to anybody, cross-referenced with every thing you like, every link you’ve clicked on, and the same data for every person you’ve connected with on Facebook’s gigantic servers. This is how Facebook, and Google, make their money – and their algorithms can crunch this mountain of data into such fine informational paste that there are recorded instances of advertisers guessing that women are pregnant before they know it themselves. This is where the value lies: Facebook isn’t the product that gets sold to advertisers, you are.

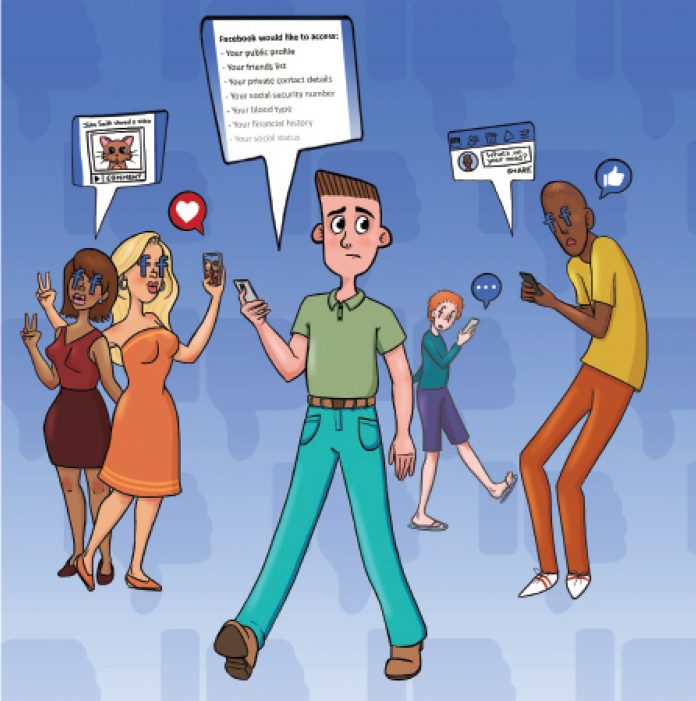

It’s easy to read this and think “You’re paranoid. Facebook’s algorithms are rubbish – they keep advertising things I hate.” This is true for me, at the moment, but the current limitations on how accurately my data can be crunched don’t mean that I’m okay with that data being stored indefinitely and sold on to third parties. Many of us wouldn’t be comfortable if that private data was used when we’re applying for a new job, or trying to enter a foreign country, but without proper controls there’s every chance it could be in the near future. We should also be worried about conscious design decisions that encourage us to create more activity data for Facebook to profit from. Apps and pages are forever asking our permission to access the data, and quite often we give it without a second thought. The site arguably encourages negative human interactions, in the form of political arguments, or just personal ones – because any engagement is good engagement as far as Facebook is concerned. It also makes design changes that encourage the compulsive activity of refreshing your feed, which scientists have shown produces a tiny, yet addictive, jolt of pleasure in our brains. Perhaps the only solution is to remove this digital parasite from our lives?

Delete your account Y/N?

Facebook is now so ubiquitous in society that disentangling our lives from its clutches is far easier said than done, and similar arguments about the malign effects of corporate power have been levelled at every new form of media. There’s also an obvious counterpoint, which is that Facebook and services like it can foster positive human interactions. The aunt in my example might not be a racist – she might experience real benefits from seeing the lives of nieces and nephews who live in a different town, from chatting to people who are too busy to schedule a phone call, or by learning more about life from somebody who lives in a different culture. I’m still in contact with most of the Americans who formed my first circle of Facebook friends, although ironically a lot of the discussions we now participate in revolve around the issues brought up in this article. There are really two ways to address the negative effects of social media consumption, and they aren’t radically different from the advice I might once have given in a similar debate about mobile phones, or television, or the printed newspaper. The first is that it’s essential to take personal responsibility for the way you consume media, and the kind of behaviour this prompts in you. Spend less time responding to disagreeable aunts and more time fostering positive interaction with people who can stay calm. Think about things before you share them, and remain cynical about the motivations and biases of people, including yourself, as well as media organisations. The consistent failure of our society to follow this advice, and to ignore the importance of media literacy, has lead to some really terrible outcomes in supposedly-free democracies. The other way to address this is to do whatever you can to ensure that gigantic corporations are regulated by government and held to account in the ways they make their money. This is a massive task, and seems almost impossible in an era where we’ve come to accept international media oligopoly, but encouraging us to give up on regulation is a deliberate strategy on behalf of massive corporations. Facebook will easily survive its current tangle with the US government, but we need to make sure we demand concrete political action to see some of its power being held to account. Like and share if you agree.